That morning, I sat in the common hall of the hostel, typing my diary on my iPad. Everyone else was asleep or slowly preparing their departures. I had my headphones on, music flowing softly, fingers dancing over the screen.

Two tall men entered the room and sat on the same couch as me. I noticed them only faintly at first—tired eyes, tattered sandals, and clothes worn thin by either time or hardship. A faint, familiar sound in their voices tugged at me, but I didn’t give it much thought. I had other thoughts to put into words.

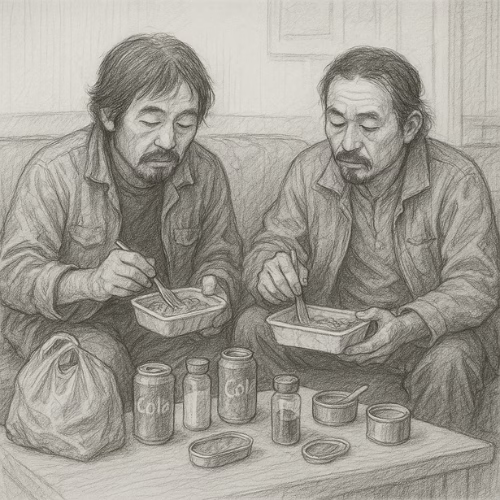

Then came the smell. They opened a container—tuna, perhaps—and the scent diffused across the room like a curtain being drawn open. I glanced at them again: dark hair, dark skin, quiet, composed movements. They looked like they came from somewhere in South Asia—maybe Nepal, maybe Bangladesh, maybe Tibet.

And then I heard it.

Through the muffled edge of my song, I caught their words. I paused, lifted my headphones—and yes. I knew that language.

Japanese.

I stared for a moment in disbelief. These men—so frugal, so weathered—were Japanese?

I began to observe their behavior: the way they unpacked, the small pepper and salt bottles they carried themselves, the way they treated each item like a tool from home rather than something disposable. Their things were old—stained fabric bags, dented lunch boxes, clothes bordering on rags. Still, nothing about them was dirty. Just… deliberate.

And I remembered.

*ੈ✩‧₊˚

My father’s voice echoed back to me from my earliest years. He always traveled with torn luggage—cheap, stained, sometimes patched. I was just a child, but I could already distinguish what looked good from what didn’t. Even then, it confused me.

“Ba, why do you carry this?” I asked.

And he told me a story in Vietnamese.

“Ngày xửa ngày xưa, có một ông lão giàu có.

Ông ta luôn gánh hai gánh trứng vịt, tóc tai bù xù, quần áo rách rưới.

Một tên trộm nhìn thấy ông ta đáng thương quá, không có gì để lấy,

Nên quay lại… mua đồ ăn tặng ông.

Ông lão ăn xong, cảm ơn tên trộm, rồi lật gánh trứng vịt lên—

Dưới đó là vàng. Ông cười, bỏ đi.”

(“Once upon a time, there was a wealthy old man.

He always carried two baskets of duck eggs, his hair messy, his clothes tattered.

One day, a thief saw him and thought he looked so pitiful, there was nothing worth stealing.

So instead, the thief turned back… and bought him a meal.

The old man finished the food, thanked the thief, and then lifted the baskets of duck eggs—

Underneath was gold. He smiled… and walked away.”)

And then he turned to me and said:

“Con à, ra đường đừng loè loẹt. Đừng để ai nhắm vào mình.”

(“My child, don’t dress too flashy when you go out. Don’t make yourself a target.”)

From that day, I started to carry wallets so old they looked worthless. I placed a few coins inside—just enough for the day. The kind of wallet a thief wouldn’t even bother with.

To this day, not a single one has been stolen.

And maybe—maybe those two Japanese men had learned the same lesson.

The lesson of the man with the duck eggs and the gold beneath.

*ੈ✩‧₊˚

And then I remembered another.

Years ago, my mother worked at a government office. One day, an old man visited. A foreigner.

His bag was ripped, zipper broken, clothes faded. He asked politely to speak with the director.

But the boss turned him away—said they were too busy, that he didn’t look important.

That same man visited a different city. That city welcomed him.

They treated him kindly. Listened. Asked nothing of him.

Two months later, that other city received millions in aid.

From him.

A billionaire, traveling the world alone, disguised as someone who had nothing.

My mother said it was the best lesson her boss ever learned—and the most expensive one, too.

*ੈ✩‧₊˚

Funny, isn’t it?

The loudest people I’ve met—the ones always bragging about their investments, their fine dining, their “generous” tips—couldn’t even pay rent without borrowing.

People wrapped in designer clothes, driving luxury cars, wearing branded perfumes—buried in debt.

The quiet ones—like the man with duck eggs, or the tuna at the hostel—often carry gold underneath.

And no one ever sees it, because no one ever looks.

As for me, I’ve come to believe:

Simplicity is peace. Minimalism is freedom.

And sometimes, true wealth is knowing when not to shine.

*ੈ✩‧₊˚

I began to pack.

Tomorrow, I’d be departing.

Where to, I still didn’t know.

But somehow, it no longer mattered.